Slipping on autumn leaves

Posted: | Updated: | Tags: train transport

It’s that time of year again, pumpkin spice lattes are in at Starbucks, sweaters are making their way out of storage and leaves are falling off trees. That last point concerns this thread more than the others. Damp leaves and train tracks are not the best match.

Wheel-rail contact and adhesion

The train wheel and rail meet on a very small surface area, called the contact patch. That small area must have enough friction to start and stop the train. The term adhesion is used to refer to the coefficient of friction, or grip, between the rail and the wheel1. Adhesion is measured in Mu (μ), which is a decimal number between 0.0 and 1.0 (or more than one if the force of friction is greater than the normal force). The lower this value the more slippery the contact patch is meaning there’s less friction. Typically more grip is required to start a train than the stop it.2

A lack of friction between the wheel and rail can cause several issues in both starting and stopping the train. Starting the train without enough grip between the wheel and rail in extreme conditions can result in ‘wheel spin’. This is when the wheels rotate without moving the whole train causing damage to the wheel and track in the form of flat spots in severe cases. More commonly this increases the time required to accelerate which means a lower frequency of trains is possible. If this is not accounted for in the timetable it will affect the train operators overall punctuality. Low-adhesion conditions can also be just as problematic during braking and arguably more dangerous. All the same concerns about punctuality apply, along with damage caused by wheel slide, with the added possibility of station overruns and signal passed at danger (SPAD) incidents. The latter could be dangerous if the next block of track is occupied by another train. Lastly, as mentioned before, increasingly longer brake and acceleration times also eat into the timetable causing delays if left unaccounted for.

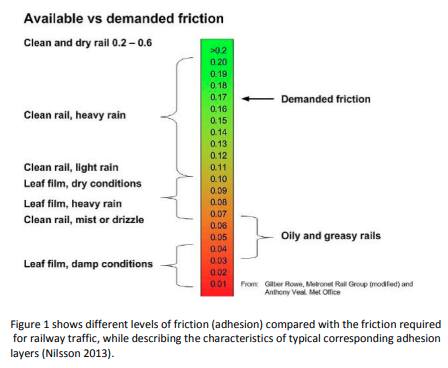

This graphic visualises the different levels of adhesion by track contaminants.

Such low-adhesion environments can be a result of several factors including weather. Heavy rain, morning dew, melted ice, and a humid atmosphere can all introduce moisture to the track. Industrial areas can leave grease and oils on the track adding a layer of slipperiness between the steel-on-steel contact patch. In Autumn, leaves falling onto the track is a well-known and common cause of extreme low-adhesion environments as they get crushed under the wheels forming a slippery pulp. The above graphic from Thommesen’s paper2 illustrates the levels of adhesion by various track contaminants.

Preventing low-adhesion incidents

When looking specifically at falling leaves during autumn, there are a few methods of prevention that can be implemented to help.

First, and maybe most obvious, is trimming back the tree line near tracks. Fewer trees and less vegetation near tracks means fewer leaves that directly land on the rail, fences can also be placed in more troublesome areas as extra protection3. These fences also act as a reminder to the driver that they’re approaching a potentially slippery area2.

This segues into the second method of preventing incidents, which is providing notification to drivers. Warning the driver before low or extremely low adhesion sections ensures they can apply defensive braking mechanisms and adjust driving behaviour according to recommendations set by the infrastructure provider or train operator21. A lot of this is already tuned in and applied by the train’s Wheel Slide Protection (WSP) system but manual intervention may be required in extremely low-adhesion situations. To add, weather forecasts can be reviewed by looking at moisture and wind so warnings can be sent out prior to anticipated low-adhesion conditions.4 This ties closely with driver training, an old and informative training video from British Rail has been referenced in writing this post, it’s worth a watch.

Adjusted driving behaviour and defensive braking may also include the use of sand and magnetic track brakes (MTB) where applicable. Applying sand to tracks may be one of the oldest methods to increase friction on the wheel-rail interface. Many examples online typically point sand boxes and pipes on steam locomotives but this method of creating friction is still very much in use today. The following screenshot was taken from an anime titled “Rail Romanesque”, the third episode briefly mentions the use of sand on steam locomotives to prevent wheel slip.

Sanders used both on locomotive and self-propelled (electric and diesel) trains have proven very effective in the UK,5 Germany4 and other countries2. It’s also quite commonly used on trams. Simply put, sand is ejected out of a nozzle onto the track to increase the friction between the rail and the wheel. This may result in additional problems, such as too much sand on tracks, interference with switches (also called points), or the detection of trains on the track2.

Locations of magnetic track brakes.

Apart from sand and adjusting driving behaviour for better traction control, magnetic track brakes (MTB) can also be used. MTBs are brake shoes that can be lowered to the rail magnetically adding more friction typically during emergency braking.2 Research conducted by Arias-Cuevas has shown that two or more MTB brakes on a VIRM used during braking on contaminated rails can improve adhesion. However, this demonstrated to be less effective between 0-40 km/h, and more care needs to be taken maintaining the brake shoes as frequent use reduces their usable remaining life.4

Finally, we will cover the use of sandite to increase adhesion. This is a metal and sand gel that can be sprayed onto the tracks. The UK experimented by applying sandite through nozzles at trains traveling at speed but were unhappy with the results, as it typically requires slower, more specialized equipment.2 However, in the Netherlands eight local (Sprinter) trains are used to apply sandite during passenger services.23 According to Prorail, wooded areas and places where trains usually have to change speed, such as stations, are targeted.36 This eliminates the need for specialized equipment and any adjustments to the passenger rail timetable. These eight trains are Sprinter Light Trains (SLTs) and took over the task after the previous sprinter rolling stock, the Stadsgewestlijk Materieel (SGM), was decommissioned in 2022.7

Fin

This post was written after reading through a number of academic papers, and news articles. It was quite fun to compile and I’ve tried to be as accurate as possible while not getting too technical. All the sources have been listed below. If you have any comments, or questions or have identified any errors the best place to reach me is on Mastodon.

BR - Driving During Low Adhesion Conditions The Train Channel - youtube.com ↩︎ ↩︎

Management of Low Adhesion in European Countries orbit.dtu.dk ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Gladheid op het spoor NS - youtube.com ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Low Adhesion in the Wheel-Rail Contact - Oscar Arias-Cuevas repository.tudelft.nl ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Variable rate sanding improves braking www.railjournal.com ↩︎

Hoe werkt de stroefmakende gel Sandite op glad spoor? www.prorail.nl ↩︎

NS zet speciale SLT Sprinters in voor herfstmaatregelen op het spoor www.treinweb.nl ↩︎