Is Amsterdam's metro really a metro?

Posted: | Updated: | Tags: status train transport

Amsterdam is a busy city with residents, businesses and visitors often talked about for its good urban planning, offering a walkable city that is still accessible by car, train, metro, tram, and bus. To those who have lived in or traveled around Amsterdam you will have come across the metro and their blue cubes with an “M” and red R-NET band at the bottom. If you’ve taken the time to travel on the Amsterdam Metro, does it seem like a typical metro?

I know it lacks a lot of the underground tunnels common for metro networks, but I have a gripe with its frequency. On too many occasions I’ve been at a metro station waiting for it to arrive, counting down the minutes on the display, wishing it were more like Paris, Madrid, or the London Underground. In the past, I’ve seen the same point brought up by others online usually with angry responses asking if the existing 6 departures an hour weren’t enough, or that we are demanding too much from the system. Am I expecting too much? Are my comparisons with these other rapid transit systems unfair? I spent some time looking into how other metro systems operate to draw a better comparison of where Amsterdam stands.

Overview of Amsterdam’s metro

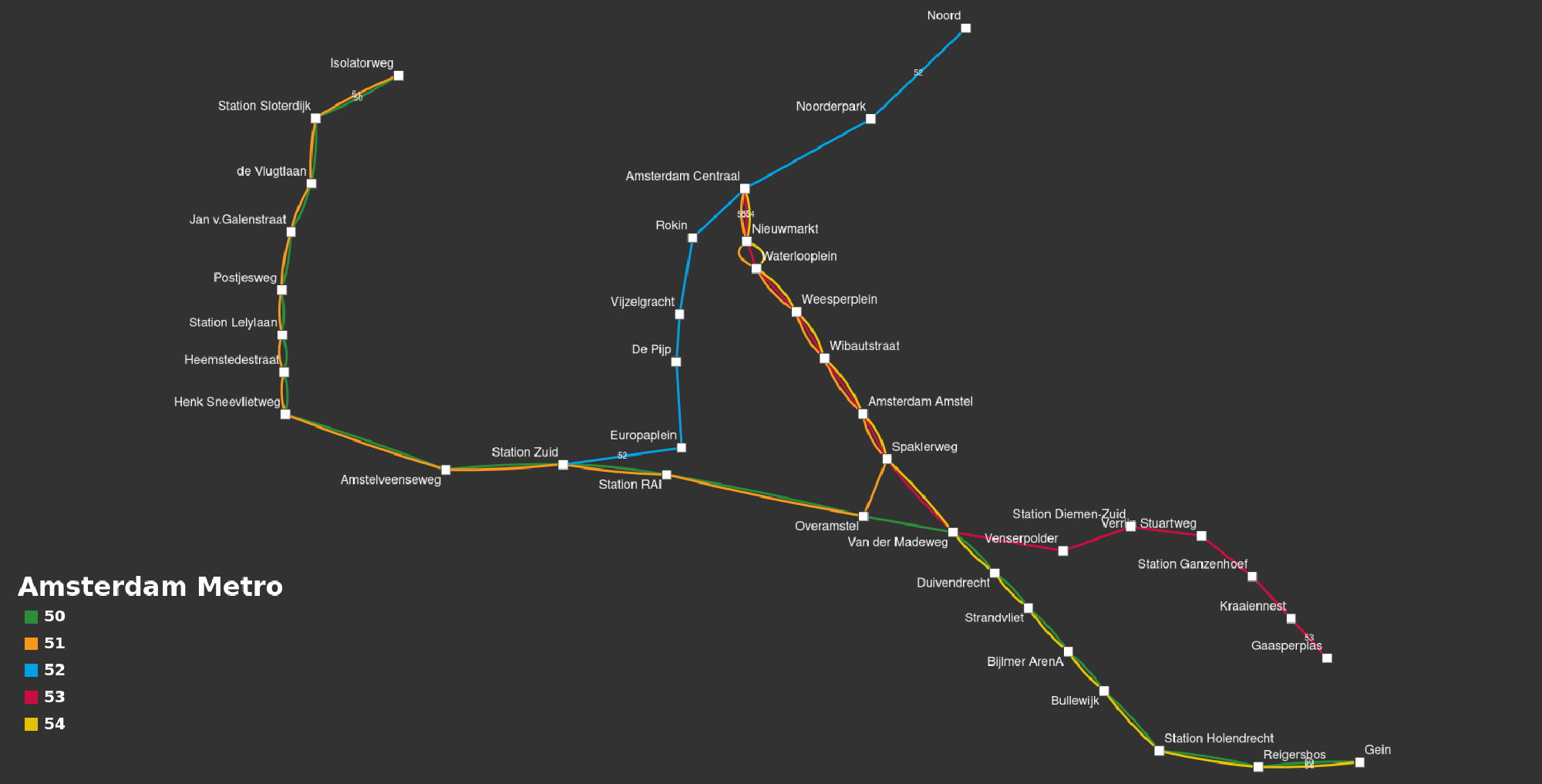

First, to level set on what we’re talking about, I’ll give you an overview of what the network looks like today and how it began. The metro comprises 5 routes, named M50 through M54, across 39 stations, 10 of which are shared with NS train stations connecting to the rest of the country via heavy rail. Many of these stations also feature opporunities to transfer to a bus or tram. The metro spans Amsterdam, Diemen, and Duivendrecht and is operated by GVB (Gemeentevervoerbedrijf) who are also responsible for operating the buses, trams and ferries in the city.

In 1970, after much planning, the infrastructure for the Oostlijn (east line) was the first to be built. This was planned to go from Amsterdam Centraal to Gein, serving the communities in Duivendrect and Bijlmer along the way. When talking about the construction of the metro, we cannot ignore the Nieuwmarkt riots in 1975. A section of the Nieuwmarkt neighborhood was set to be demolished to make room to build the underground section of the metro closer to Amsterdam Centraal. Parts of the area were rebuilt after the metro construction but for obvious reasons, this did not sit well with the residents of the neighborhood. The first part of the metro line was up and running in 1977 between Weesperplein and Gaasperplas. Later extensions were completed northwards towards Amsterdam Centraal and southward towards Gein in the next five years. Today routes M53 and M54 run on the Oostlijn, where they diverge at Van der Madeweg, M53 then heads to Gassperplas and M54 to Gein.

In the late 1980s, the construction of the Amstelveenlijn began, it branched from the Oostlijn at Spaklerweg heading towards Amstelveen via Station Zuid. This was built as a tram line so the rolling stock had to use third rail up until Station Zuid where it then switched to the overhead line. Unconventional for a metro and also complex to operate. It’s no surprise that today the metro only runs up to Station Zuid and the rest of the infrastructure towards Amstelveen has been converted to tram only. It’s for this reason I’ve left Station Zuid to Amstelveen section out of the map above keeping it simple.

Next to be built was the Ringlijn which was completed in 1997, while not fully circular it does curve along its path between RAI and Isolaterweg. Metro Line 50 operates on this infrastructure to Gein. While it was initially planned to use overhead lines on this route, like trams, it was then scrapped and third rail was installed. It was because of this the stations along the Ringlijn were also built to accommodate light rail (tram) vehicles, but this was later adjusted so metro cars from the other lines could also be used. The line runs by the heavy rail track along the west and south of Amsterdam and so features many transfer opportunities to NS trains connecting you to the rest of the country.

Lastly, the Noord/Zuidlijn opened for service in 2018. The infrastructure is used solely by M52 and goes from Amsterdam Noord to Zuid, via Amsterdam Centraal. Many new stations had to be built as the line didn’t intersect with the existing metro network. Even in areas where transfers to the other metro lines are possible, M52 uses its own infrastructure. This line was also equipped with communications-based train control (CBTC), a singaling system that increases the accuracy of locating a train on the track. At launch which was then planned to be rolled out to the other metro lines as well, this is important for later on.

Characteristics of a metro

When people complain about the Amsterdam metro, at least when I do, it’s usually about the timing and frequency of trains. Metros, in my mind, are associated with quick stops and frequent stops at stations throughout the day. To put that numerically, it comes out to about one train every 3-4 minutes, especially during rush hour. NotJustBikes, on his podcast The Urbanist Agenda, phrased it very well when he said “You don’t want to wait 6 minutes for an elevator, people get upset if they’re waiting more than about a minute and a half for an elevator… metros are certainly right up there with nearly elevator level of frequencies.” This episode also featured RMTransit, and they talked about why the Amsterdam metro is so obscure and why it “kinda sucks”.

Signaling

Metros are getting increasingly automated, which in turn allows for higher frequencies and better timetable reliability. Increasing automation means drivers don’t have to make decisions based on signals per block, manually adjust brake force, or determine the acceleration curve to reach the maximum speed. Having the train make the decisions based on a moving block allows the operator to reduce the distance between each train on the track and for the system to control the train’s acceleration and deceleration. This is were signaling systems like CBTC come into play. For example, some of Paris’ busiest metro lines have been automated, lines 1, 4, and 14 are fully automated with lines 1 and 4 running with driverless operation (GoA4). On line 4, the headway was reduced from 105 to 85 seconds allowing trains to run closer together.1 There are plans to expand this to other lines as well. You’ll be able to find similar case studies in other urban cities where CBTC with moving-block signaling and fully autonomous (GoA4) operation are here or on the horizon. In such cases, it’s common to see the interval between trains being 100 seconds or less.

How does Amsterdam fare up to other cities? The new Noord/Zuidlijn opened in 2018 is equipped with CBTC signaling supplied by Alstom, who claimed this enables GVB to run a train every 90 seconds.2 By testing the system on this line the hope was to then gradually apply CBTC to the other lines used by M50, M51, M53, and M54 in 2021. So far so good, a promise that doesn’t seem too far-fetched given what other metro systems are doing. After several tests, and phased introduction of CBTC, the transition to the new system didn’t go as planned. GVB eventually had to revert to the old system after several disruptions3. AT5 reported eleven disruptions in 2021 and another in 2022 before the article was written in January 2022 all pointing back to the use of CBTC.4 According to the interviews they conducted with traffic controllers and train drivers the rushed delivery of the system and the use of older rolling stock just didn’t work well with CBTC. GVB has been gradually replacing its equipment from the 1990s with the new M5 units, used on the M52 line, built by Alstom and the M7 units built by CAF, but this is expected to take another few years until it’s complete.

Infrastructure

Another oddity I’ve seen on the Amsterdam metro is the amount of shared tracks between lines. In what I call the trunk, between Amsterdam Centraal and Sparklerweg, Metro lines 51, 53, and 54 all use the same track. It is great from a passenger perspective if I wanted to travel to any destination on the trunk, I’d have to stand at the correct platform depending on the direction I’m going and take any metro train regardless of line since there’s no dedicated platform per line. Some other examples of this are lines 51 and 50 which share the tracks between Isolaterweg and Overamstel, and lines 50 and 54 which share the tracks between Van der Madeweg and Gein. Only M52 has the track dedicated to the line itself, this also relates to the difficulty in implementing CBTC on the other lines. If I were to take a guess this also poses some limitations on the number of trains that can run given the current setup. It seems the infrastructure was built to favour fewer transfers going from point A to point B compared to how other metro systems work.

Capacity

I’ve mentioned the frequency of trains a lot so far, but haven’t yet touched on capacity. It’s common and expected, for regional trains to arrive less frequently at a station given the longer distances they travel but also the higher number of passengers they carry per trip. On the other hand, looking at metro trains they usually have a lower passenger capacity but run more frequently, essentially still carrying a larger number of people but over multiple trips. To understand the relation between frequency and capacity I’ve graphed the frequency against the passenger capacity of a few metro systems.

Trains per hour compared against the passenger capacity per train.

At the very top, we can see Paris lines 2, 7, and 14 all with over 30 trains per hour, Madrid line 3 has also done well with 25 trains per hour. The rolling stock used for these lines has the ability to hold between 500 to 1000 passengers. Amsterdam’s metro lines 50, 51, 53, and 54 all have a frequency of 6 trains per hour during peak capable of carrying 500 to 960 passengers depending on which rolling stock is in use and the configuration. The outlier for Amsterdam is line 52, running on its own infrastructure using CBTC signaling, at 10 trains per hour with the ability to carry 960 passengers.

Taking the frequency and multiplying that by the train capacity we can get the passengers per hour per direction (PPHPD) allowing us to measure the theoretical capacity of each line. The following table ranks each of the plot points above from lowest to highest PPHPD, higher being better.

| Line | Capacity | Frequency | PPHPD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amsterdam Tram 7 | 175 | 6 | 1050 |

| Berlin U1 | 330 | 6 | 1980 |

| Amsterdam M50 and M51 | 500 | 6 | 3000 |

| Berlin U5 | 330 | 12 | 3960 |

| NYC Line 6 | 252 | 18 | 4536 |

| Lisbon Azul | 350 | 13 | 4550 |

| Lisbon Amarela | 350 | 14 | 4900 |

| Amsterdam M53 and M54 | 960 | 6 | 5760 |

| Madrid R | 480 | 12 | 5760 |

| Copenhagen M2 | 300 | 20 | 6000 |

| Zurich S3 | 1035 | 8 | 8280 |

| Amsterdam M52 | 960 | 10 | 9600 |

| Madrid Metro Line 8 | 609 | 17 | 10353 |

| Paris 2 | 557 | 32 | 17824 |

| Madrid Metro Line 3 | 736 | 25 | 18400 |

| Paris 7 | 574 | 34 | 19516 |

| Berlin U7 | 1920 | 12 | 23040 |

| Paris 14 | 932 | 35 | 32620 |

Amsterdam’s lines 53 and 54 can achieve a PPHPD value of 5760, assuming it’s running the newer M5 trainset with a higher passenger capacity.5 This is equivalent to Madrid’s R line which runs twice as much but with half the passenger capacity. However, Amsterdam’s line 52 doesn’t compare well to Madrid’s line 8 and 3 which runs 17-25 trains per hour at higher passenger capacities than Amsterdam’s M5 trains. Amsterdam does do well when compared with Lisbon’s metro and NYC’s line 6, all of which run way more frequently but carry fewer passengers on each trip.

Looking at the capacity of each line, including both the number of passengers and frequency, Amsterdam doesn’t seem so bad after all. If it were up to me, I would still trade passenger capacity for frequency if possible, reducing overall wait times at the platform. Keeping the same PPHPD score to ensure the passengers spread out more between trains.

Bottlenecks in operating metros

Simply saying, “GVB should run more trains on the metro lines” doesn’t mean they automatically can, if they could surely they would. We’ve already covered a little bit about the limitation of signaling when discussing the infrastructure. Both Alstom and GVB did seem to give it a go to no success, old rolling stock and shared infrastructure between metro lines made it more complicated than anticipated. To add to that, GVB has said public transport ridership has risen since the pandemic, but they still lack the staff despite ramping up their hires this year. This adds another hurdle in deploying more trains on tracks, even if the signaling issue was not there.

Another bottleneck I hadn’t previously anticipated is traction power. In the upcoming 2024 timetable, GVB announced they would increase the frequency of the M52 line to 12 trains per hour, instead of the existing 10, during peak times. They have, however, mentioned this would only be possible if they see the traction power produced is enough to run the trains on the line. If it isn’t GVB will stick to the original 10 trains per hour.6

Fin

This weekend Amsterdam’s public transport will switch to the 2024 calendar, I would have hoped for some better changes to the metros schedule but attempting 12 trains per hour on the M52 line is a good start. If there weren’t any bottlenecks in Amsterdam’s metro system to permit more trains, would the Amsterdam metro system actually be used more? I started off describing Amsterdam as a city accessible through multiple modes of transport. Amsterdam has a dense tram network, with streets designed for walking and cycling and busses to fill in all the gaps. The metro does have some good competition. Would a better metro system actually benefit Amsterdam?

Let me know your thoughts, or if there are any corrections to this post on Mastodon, @PeskyPotato@hachyderm.io.

Update 2025-03-16: The Vervoerregio Amsterdam has proposed changes to the Amsterdam Metro network to accomodate a growth in the number of passengers by 2027. Outlined are four options which the public can vote on, the mainly target changes to the Oostbuis (what I called the central trunk) to reduce the number of lines increasing reliability and frequency. The first three options allows for at least 10 trains per hour during peak, and the fourth option at least 8 trains per hour, both of which are good improvements. Reducing the number of lines does mean changes for some passengers at Van der Madeweg when travelling towards and away from Centraal Station.

Fully automated metros introduced on line 4 in Paris www.railtech.com ↩︎

New Amsterdam metro line drives fully automatically from station to station www.deingenieur.nl ↩︎

Vanaf 24 oktober rijden we weer met het nieuwe metrobeveiligingssysteem over.gvb.nl ↩︎

Structurele problemen teisteren nieuw metrosysteem: “Geen verkeersleider staat er nog achter” www.at5.nl ↩︎

The M5 rolling stock, from Alstoms Metropolis family, is a six-car trainset that carries 960 passengers according to Alstom’s Press Release. Do note, GVB also uses older rolling stock on lines 53 and 54 with a lower passenger capacity. ↩︎

Geen netwerkwijzigingen in aangepast Vervoerplan 2024 over.gvb.nl ↩︎